The Cultured Abalone

How a California Farm is Reviving a Pacific Delicacy

On a quiet stretch of Santa Barbara's Gaviota Coast, where craggy cliffs dip into the surf, a slow and ancient rhythm pulses within fiberglass tanks. The Cultured Abalone Farm—one of only two red abalone aquaculture operations in the United States—isn't just producing seafood—it's resurrecting it.

A Comeback Story, Told in Shells

Red abalone, Haliotis rufescens,[1] have been central to coastal California's foodways for thousands of years.[2] Long before culinary trends or fishing commissions, abalone were prized by local Indigenous communities for sustenance and ceremony.[3] The abalone meat was a cherished protein, harvested from kelp-laced waters while the shells, iridescent and banded with natural pigment, were transformed into regalia, fishing hooks, and trade.

In the 1800s, waves of immigration launched an industry boom. Most Euro-Americans viewed abalone as an inedible oddity, but in China, abalone was an overfished delicacy. Chinese immigrants in California recognized a golden opportunity to tap an unexploited market, and began drying and exporting abalone collected from the shoreline.[4] At the peak of California's abalone industry in the 1880s, fishermen of Chinese descent working in the Northern Channel Islands processed approximately 40 tons of dried black abalone meat and shells annually, making it a multimillion dollar trade.[5] However, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and the combined forces of discrimination, exorbitant taxes, and exclusionary legislation threatened a decline in the abalone trade.[6] Japanese hardhat divers immediately filled this vacancy, and began descending into rocky coves to harvest abalone that flourished beneath the tides. In 1900, California counties passed ordinances that made it illegal to gather abalones from less than twenty feet of water, which benefitted Japanese free divers. By the 1940s, the fishery was flourishing.[7]

Then came the decline.

Decades of overharvesting, climate-driven kelp loss, and unchecked purple sea urchin populations[8]—voracious reef crawlers that raze underwater kelp forests to barren rock—devastated abalone stocks. One by one, fisheries closed, with all commercial abalone fisheries ceasing to exist by 1997. The final nail came in 2018, when the last recreational red abalone fishery was shuttered indefinitely.[9] These moratoriums have made farmed abalone the only legal option for this Pacific delicacy.

Enter The Cultured Abalone.

A Living Extension of the Sea

The afternoon I arrived at The Cultured Abalone, a heavy fog still clung to the cliffs. My guide, Andie Van Horn, met me at the gate in a red pick-up truck, and led me past the wind-whipped trees to a small outpost adorned in iridescent shells.

The Cultured Abalone is situated near an ephemeral river and in an area called the Dos Pueblos. The area was named after two Chumash villages located right next to each other, separated by a small stream and an estero.[10]

On Saturdays, The Cultured Abalone’s team opens the farm up to the public for walking tours. Chefs, seafood lovers, and those curious about diving into the world of these peculiar mollusks can spent an afternoon with their guardians learning about their history and life cycle.

Andie led us to a large aquaculture flow through system, and pointed toward the hillside, "that pipe brings in water straight from the Santa Barbara Channel," she explained. "No filtration beyond a mesh that keeps the fish out. The abalone get the real deal."

Founded in 1989,[11] the farm has embodied a living extension of the Pacific Ocean. Seawater drawn straight from the Santa Barbara Channel feeds shaded tanks designed like rocky kelp forests, complete with crevices and cool currents. Each day, more than two million gallons of cold seawater are pumped throughout the entirety of the farm. This ecosystem-engineered approach nurtures every stage of the red abalone, from sesame-seed larvae to market-ready snails four years later. It's a system that blurs the boundary between wild and farm—more extension than imitation.

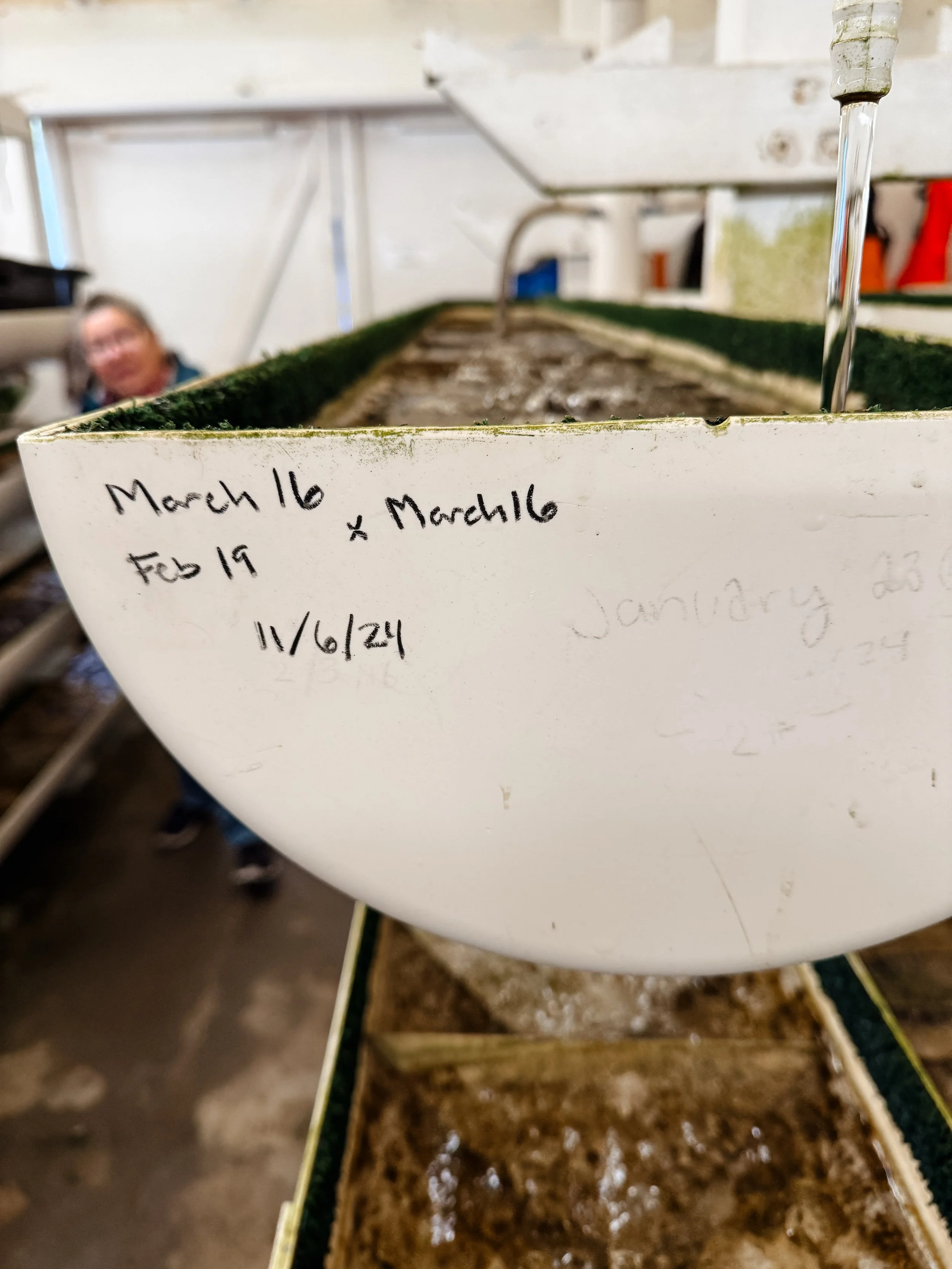

The story of each red abalone at the farm starts small—microscopic even. Peering into the hatchery, visitors see what look like poppy seeds bobbing in five-gallon buckets of seawater. These abalone larvae, just a few days old, are the beginning of a three- to four- year journey from tiny speck to shimmering mollusk.

Red abalone are the largest species of abalone in the world, with shells growing as large as a foot in length.[12]

Plucking a shell from a bubbling tank, Andie pointed to five concentric holes running along the shell. She explained the holes were respiratory pores that allow for water to flow under the edge of the abalone’s shell, over the gills, where oxygen is absorbed and carbon dioxide is expelled. As an abalone grows, older pores are sealed off and newer ones open up near the outer edge of the shell.

Andie flipped the abalone over to reveal it’s peculiar anatomy. The abalone’s burnt orange foot contracted in a dance-like swirl. In time, two pitch black retractable stalks emerged from the shell, bearing myopic eyes. Its long, jet-black tentacles waved with a peculiar rhythm.

A sudden yelp pulled our group out of its abalone trance dance—a woman had placed an abalone on the palm of her hand, and it had begun to sluggishly propel its way down her forearm. Laughing, she attempted to pull it from her arm, but it clung to her like a suction cup. Once freed, it let behind a shimmer of mucous.

As they grow, the abalone graduate to shaded outdoor tanks, carefully engineered to mimic the topography of their natural rocky habitat.

The abalone's diet is equally precise—a rotating menu of locally wild-harvested Macrocystis pyrifera (giant kelp), and farm-cultivated ogo (Gracilaria pacifica) and red dulse (Palmaria spp). No land-based proteins. No antibiotics. Just seaweed—and lots of it. In fact, twice a week, a specially-designed vessel fitted with an aquatic lawn-mower trims the surface canopies off of the giant kelp forests off of Santa Barbara, and delivers the marine harvest to the growing abalone with tide-fresh immediacy.

The results are beautiful. Literally. The abalone's varied algal diet etches itself into their shells, painting bands of red, green, and brown—living records of the kelp they consume. Nestled in their tanks, the abalone creep slowly over each other, rasping algae from shells with their radulae, preventing the shaggy camouflage seen in their wild cousins.

The Cultured Abalone Farm houses tanks of older, larger red abalone, which are kept as broodstock, the parents of future generations of farmed abalone. All of the abalone on site are bred from farmed abalone broodstock, as opposed to captive wild abalone. Andie shared that a 1.5 inch abalone may spawn 10,000 eggs or more at a time, while an 8 inch abalone may spawn 11 million or more eggs.[13]

About one million abalone are cycled through the hatchery and grow-out tanks each year, and sold live across the United States, Canada, and the Pacific Rim. The Cultured Abalone also extends sales into the academic and analytical communities by providing abalone for water testing and by supporting a wide diversity of research initiatives. The Cultured Abalone are also working with several efforts to breed wild abalone to be replanted into areas impacted by the 2015 Refugio oil spill.

From Barrens to Brilliance: The Purple Hotchi

But The Cultured Abalone isn't just reviving one marine delicacy—it's reimaging another.

After the abalone, Andie ushered me toward another section of the farm—this one housing their latest innovation, the purple hotchi.

The Cultured Abalone also serves as a "ranch" for Purple Hotchi sea urchin rescued from the wild. Derived from the English Romani word "hotchi-witchi," meaning "hedgehog" or literally translated to "forest urchin," purple sea urchins have a complicated reputation—a pest with little culinary value. While divers prize the larger red urchins for their plump, consistent uni, purple urchins often yield little more than disappointment and empty shells.

Beneath the waves of the California coast, purple urchins scuttle with quiet menace. With an insatiable appetite and no real natural predators, they raze kelp forests to rubble, leaving behind swaths of underwater desert known as urchin barrens. These once-thriving marine gardens are stripped down to bare rock, and no other marine species can thrive.

And what happens when the kelp is gone?

The urchins stay put—starving but stubborn. Marine biologists call them "zombie urchins"—a phrase that sounds mythic but is all too real. These urchins do not have enough food available to produce roe and, devoid of roe, they are ecologically disruptive and economically worthless.

While their crimson cousins—the red urchins—have long earned a place on the tables of fine dining restaurants throughout the world, purple urchins have been left behind. Lacking commercial value and natural predators, these zombie urchins have multiplied unchecked, carpeting the ocean like a cautionary tale.

But The Cultured Abalone saw something else—potential.

Partnering with local commercial divers, The Cultured Abalone collects starving zombie urchins from decimated kelp forests, and brings them to the farm. Over 10-12 weeks, these urchins are fed farm-grown seaweed, fattened into plump roe-laden delicacies and reborn as "Purple Hotchis," as ecologically redemptive as they are delicious. This ecologically healing initiative clears kelp-scouring populations while delivering a buttery uni ripe for tasting menus.

On site, I tasted one—briny, creamy, with a whisper of sweetness that lingers like surf on sand.

Learn More

Want to see The Cultured Abalone for yourself? Good News! The farm offers walking tours of its land-based operations on Saturday’s! Check out The Cultured Abalone’s Events page for tickets. Watch the lifecycle unfold. Smell the kelp. Hold a three-year-old abalone in the palm, and feel the slow pulse of something rare—a delicacy reared with intention, nestled in seaweed, and shaped by time.

For other great resources, check out the works of marine biologist, Oriana Pointdexter, as well as the PBS Documentary, Hope in the Water.

Resources

[1] Abalone belong to the family Haliotidae and the genus Haliotis, which means "sea ear," referring to the flattened shape of the shell. abalone.pdf

[2] In the wild, red abalone are found in the intertidal zone to water more than 590 feet deep, but are most common between 20 and 130 feet. Cowles, D. (2005). Haliotis rufescens. Archived 2015-02-25 at the Wayback Machine Biological Department, Walla Walla University. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

[3] Red Abalone Gardens: Cultural Keystone Species and Implications for Marine Conservation and Restoration | Society of Ethnobiology

[4] Braje, Todd., J, “How Chinese Immigrants Built—and Lost—a Shellfish Industry.” Sapiens, https://www.sapiens.org/archaeology/california-abalone-chinese-immigrants/

[5] Braje, Todd J., et al. “Fishing from Past to Present: Continuity and Resilience of Red Abalone Fisheries on the Channel Islands, California.” Ecological Applications, vol. 19, no. 4, 2009, pp. 906–19

[6] Ashley, Melissa, et al. “Roy Hattori and the Japanese American Abalone Fishery of Monterey Bay.” Sea History 188, Autumn 2024, available at https://seahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/14-21-SH188-Hattori.pdf. Retrieved July 21, 2025.

[7] Dating back to the early 1900s, central and southern California supported commercial fisheries for red, pink, green, black, and white abalone, with red abalone dominating the landings from 1916 through 1943. Landings increased rapidly beginning in the 1940s and began a steady decline in the late 1960s which continued until the 1997 moratorium on all abalone fishing south of San Francisco. Extremely low populations lead to the listing of white abalone as a federally endangered species in 2001 and black abalone were listed in 2009

[8] In recent years, purple sea urchin populations have greatly increased along the northern California coast and have made the main foods for abalone (kelp and other seaweeds) so scarce that many abalone have starved to death. The increased number of shells washing ashore indicates the extent to which abalone populations are being impacted by lack of food. It has also been common to find abalone which have very shrunken bodies due to lack of food rather than a disease (see abalone disease question in FAQ). The shrunken abalone are weaker than healthy abalone and are more likely to be dislodged and killed by large waves. https://cdfwmarine.wordpress.com/2016/03/30/perfect-storm-decimates-kelp/.

[9] The poor condition of red abalone populations led the California Fish and Game Commission to close the fishery in 2018. California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) surveys in 2018 found lower densities of abalone and numerous fresh empty shells which indicated continued high mortality. The Commission extended the closure until 2021 at their December, 2018 meeting. Subsequent surveys found red abalone populations remained in poor condition and the closure was extended to 2026 at the December, 2020 Commission meeting. The goal of the Red Abalone Recovery Plan is to develop a robust, adaptive, climate-ready strategy to support the recovery of the red abalone population to sustainable levels

[10] Dos Pueblos Chumash – Goleta History

[11] Before it was an abalone farm, The Cultured Abalone was actually the site of a cut-your-own Christmas Tree Farm, featuring Monterrey Pine.

[12] Life History Information for Selected California Marine Invertebrates and Plants. California Department of Fish and Wildlife.